DLB:アリセプトの投与が錐体外路症状の出現率を高めるか? [レビー小体型認知症]

【森 悦朗, Ikeda M, Nakagawa M, Miyagishi H, Yamaguchi H, Kosaka K: Effects of ドネペジル on Extrapyramidal Symptoms in Patients with Dementia with Lewy Bodies - A Secondary Pooled Analysis of Two Randomized-Controlled and Two Open-Label Long-Term Extension Studies. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord, 40 (3-4), 186-198 (2015)】

Abstract

Background/Aims: The aim of this study was to clarify the effects of donepezil on extrapyramidal symptoms in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Methods: Using pooled datasets from phase 2 and 3, 12-week randomized, placebo-controlled trials (RCT, n = 281) and 52-week open-label long-term extension trials (OLE, n = 241) of donepezil in DLB, the effects of donepezil on the incidence of extrapyramidal adverse events (AEs) and on the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) part III were assessed, and potential baseline factors affecting the AEs were explored. Results: The RCT analysis did not show significant differences between the placebo and active (3, 5, and 10 mg donepezil) groups in extrapyramidal AE incidence (3.8 and 6.5%, p = 0.569) and change in the UPDRS (mean ± SD: -0.2 ± 4.3 and -0.6 ± 6.5, p = 0.562). In the OLE analysis (5 and 10 mg donepezil), the incidence did not increase chronologically; all AEs leading to a dose reduction or discontinuation except one were relieved. The UPDRS was unchanged for 52 weeks. An exploratory multivariate logistic regression analysis of the RCTs revealed that donepezil treatment was not a significant factor affecting the AEs. Baseline severity of parkinsonism was a predisposing factor for worsening of parkinsonism without significant interactions between donepezil and baseline severity. Conclusion: DLB can safely be treated with donepezil without relevant worsening of extrapyramidal symptoms, but treatment requires careful attention to symptom progression when administered to patients with relatively severe parkinsonism.

Introduction

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is the second most common form of senile dementia following Alzheimer's disease (AD) [1]. The core clinical features of DLB include neuropsychiatric symptoms and parkinsonism as well as cognitive impairment characterized by deficits in attention, executive function, and visual perception [2]. The cholinergic loss and a choline acetyltransferase activity deficit with preserved postsynaptic cortical muscarinic and nicotinic receptors [3,4,5] rationalizes the use of cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) in DLB. The favorable potential of ChEls such as galantamine, rivastigmine, and donepezil has been demonstrated in previous studies [6,7,8,9,10,11]. The phase 2 and 3 trials of donepezil in patients with DLB have added to the accumulating evidence of the efficacy and safety of donepezil in terms of cognitive, behavioral, and global function in DLB, even for long durations, without increasing the risk of clinically significant safety events [12,13,14,15].

It has been reported that 25-50% of patients with DLB have parkinsonism at the time of diagnosis and that 75-80% of such patients eventually develop it [16], although the exact proportion is still controversial. In a natural course, the symptoms could worsen with a speed comparable to Parkinson's disease (PD) [17]. The cholinergic interneurons synapse on the GABAergic striatal neurons that project to the globus pallidus. The cholinergic actions inhibit striatal cells of the direct pathway and excite striatal cells of the indirect pathway. Thus, ChEIs augment cholinergic function, which may oppose the effects of dopamine on the direct and indirect pathways exacerbating parkinsonism in DLB, in which nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons have been lost [18,19,20,21]. On purely theoretical grounds, ChEI administration targeting cognitive impairment and behavioral symptoms may exacerbate parkinsonism. Despite studies showing that ChEIs did not affect parkinsonism and which did not replicate the possible untoward effects in patients with DLB or PD dementia (PDD) [22,23], concerns over a possible influence on the extrapyramidal symptoms still linger due to a shortage of evidence from large-scale, placebo-controlled, or long-term studies especially in DLB and require further confirmation.

As in diseases like DLB treatment for one symptom may precipitate others [24] and the combination or severity of the associated multiple, multi-dimensional symptoms varies by patient, a large-scale comprehensive study is essential. Our trials of donepezil in patients with DLB consist of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (RCT) and two open-label long-term extension studies (OLE) and enrolled a large group of patients that may embody patients with diverse demographic characteristics and clinical symptom manifestations, which the current diagnosis of probable DLB may encompass. We therefore developed two types of comprehensive pooled datasets from two RCTs and two OLEs of donepezil for DLB. RCTs provide information with minimized bias, while OLEs involve more patient-years of exposure to donepezil and may thus disclose adverse effects which are not observed in the parent RCTs. Using these datasets of the largest scale ever in DLB, we analyzed the effect of donepezil on the occurrence and worsening of extrapyramidal symptoms in patients with DLB.

Methods

Design of the Phase 2 and 3 Studies

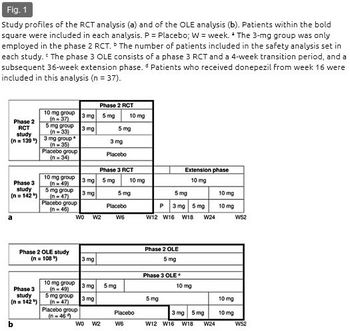

This analysis pooled the data from the phase 2 and 3 studies of donepezil for DLB conducted in Japan. The phase 2 studies, consisting of a RCT (clinicaltrials.gov reference: NCT00543855) and a subsequent OLE (clinicaltrials.gov reference: NCT00598650), were conducted as two sequential protocols. A 12-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled exploratory study (phase 2 RCT) was first conducted to investigate the efficacy and safety of donepezil at 3, 5, and 10 mg/day starting in 2007 (fig. 1a) [12]. In the patients who completed this RCT, the safety and efficacy of long-term administration at 5 mg were further investigated in the following 52-week OLE (phase 2 OLE) (fig. 1b) [13]. The phase 3 study (clinicaltrials.gov reference: NCT01278407) was conducted as a single protocol consisting of an RCT phase and a subsequent OLE phase. A 16-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled comparative study consisting of a 12-week confirmatory phase (phase 3 RCT) (fig. 1a) [14] and a 4-week transition period and a subsequent 36-week OLE phase were conducted starting in 2011 for a total duration of 52 weeks (phase 3 OLE) (fig. 1b) [15]. The aim was to confirm the superiority of donepezil at 5 and 10 mg/day for 12 weeks over placebo with regard to both cognitive function and behavioral symptoms and to evaluate the safety and efficacy of long-term administration of 10 mg/day for 52 weeks. Each study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocols were approved by the institutional review board at each participating center.

Patients

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same in both RCTs. The inclusion criteria were patients aged ≥50 years with probable DLB fulfilling the consensus diagnostic criteria [2], with mild to moderate-severe dementia [10-26 points on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Clinical Dementia Rating ≥0.5], behavioral symptoms or cognitive fluctuation [Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)-plus ≥8 (rated on 12 items: original 10 NPI items + sleep [25,26] + Cognitive Fluctuation Inventory [27,28])], and with caregivers who could routinely stay with the patients, provide information for this study, assist with treatment compliance, and escort them to required visits.

The exclusion criteria included PD that was diagnosed at least 1 year prior to the onset of dementia; focal vascular lesions on an MRI or CT that might cause cognitive impairment; other neurological or psychiatric diseases; complications or a history of severe gastrointestinal ulcers, severe asthma, or obstructive pulmonary disease; systolic hypotension (<90 mm Hg); bradycardia (<50 bpm); sick sinus syndrome; atrial or atrioventricular conduction block; QT interval prolongation (≥450 ms); severe parkinsonism (Hoehn and Yahr stage ≥4) [29], and treatment with ChEIs or any investigational drug within 3 months prior to screening. ChEIs, antipsychotics, and anti-Parkinson drugs were not allowed during the study, except for levodopa and dopamine agonists, of which only stable doses were allowed during the RCTs.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient (if at all possible) and his/her primary family member before initiating the study procedures.

Donepezil Administration

In the phase 2 RCT, the patients were randomized to placebo, 3, 5, or 10 mg/day of donepezil (placebo, 3-, 5-, and 10-mg groups) (fig. 1a). In the subsequent phase 2 OLE, all patients received donepezil at 5 mg/day (fig. 1b). Donepezil administration in the 5- and 10-mg groups started with a 2-week titration period with a 3-mg dose, which was applied in all of the studies.

In the phase 3 RCT, the patients were randomized to placebo, 5, or 10 mg/day (placebo, 5-, or 10-mg group) (fig. 1a). Since the phase 3 study incorporated the RCT and OLE phases, the duration of donepezil administration in the phase 3 OLE differed by treatment group: 52 weeks for the 5- and 10-mg groups (10 mg administration from week 24 and 6, respectively) with a 12-week overlap with the phase 3 RCT, and 36 weeks for the placebo group (3 mg titration from week 16, 5 mg administration from week 18, and 10 mg from week 24) (fig. 1b).

In the OLEs, a dose reduction to 3 mg in the phase 2 OLE or to 5 mg after week 24 in the phase 3 OLE was allowed upon emergence of a safety concern.

Summary of the Results of the Phase 2 and 3 Studies

The results of the phase 2 and 3 studies are reported in detail elsewhere [12,13,14,15]. Briefly, in phase 2, the RCT showed that donepezil significantly improved cognitive, behavioral, and global functions with good tolerability, and the OLE demonstrated that administration was well tolerated even for a long duration and that the effect on cognitive and behavioral impairment was maintained for up to 52 weeks. In phase 3, although the RCT failed to confirm a superiority concerning the behavioral symptoms over placebo, it confirmed the efficacy concerning cognitive function (one of the co-primary endpoints) without serious safety concerns. The OLE demonstrated a lasting improvement in cognitive function for up to 52 weeks, without increasing the risk of clinically significant safety events.

Datasets

The safety data regarding extrapyramidal symptoms derived from these studies were pooled in two ways: RCT and OLE (fig. 1). The datasets of the two RCTs were pooled and analyzed according to allocated treatment during the 12-week period: placebo, 3-, 5-, or 10-mg groups (n = 281) (fig. 1a). The dataset derived from all patients receiving donepezil via long-term administration [i.e. phase 2 OLE and phase 3 OLE (whole period of phase 3: RCT + OLE)] was pooled and analyzed (n = 241) (fig. 1b).

Assessment of Extrapyramidal Symptoms

The influence on extrapyramidal symptoms was evaluated according to the incidence of extrapyramidal adverse events (AEs) and the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) part III [30]. To reduce interrater and intrarater variability, an advanced rater training was conducted, a fixed rater was involved in the assessment of each patient in principle, and an elaborate monitoring was made throughout the study period. Of all the AEs which occurred during the studies (coded according to the Preferred Terms of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities), the following were identified as extrapyramidal AEs after discussion by the central committee: parkinsonism, rigidity, tremor, camptocormia, gait difficulty, and akinesia. The UPDRS part III was conducted every 12 weeks in the phase 2 RCT and in phase 3, and every 24 weeks in the phase 2 OLE.

Statistical Analysis

This secondary analysis was based on the safety analysis set of each study, which comprised all patients who received at least one dose of donepezil and had safety assessment data. For the analysis of the RCTs, the incidence of extrapyramidal AEs was summarized by treatment group and compared between the placebo and each active group using Fisher's exact test. The change in the UPDRS part III total and subscale score from baseline was compared between the placebo and each treatment group using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with the baseline values as covariates. Subscales were predefined as the following four symptoms: tremor, akinesia, rigidity, and postural instability and gait difficulty, with score ranges of 0-28, 0-36, 0-20, and 0-16, respectively [31,32]. For the analysis of OLEs, the incidence of extrapyramidal AEs was calculated. The UPDRS part III scores were analyzed using Student's paired t test.

To identify any potential baseline factors that may contribute to the extrapyramidal AEs, the incidence was calculated for subgroups stratified by the potential factors, and univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were subsequently conducted. Potential factors included endogenous factors (sex, age, and body weight) and symptom-related factors [UPDRS part III score, Hoehn and Yahr stage (≤2 or 3), and use of anti-Parkinson drugs (use or nonuse)]. In multivariate analyses, either the UPDRS part III score or the Hoehn and Yahr stage was included in the model because of the high correlation between them. In the analysis of the RCTs, the interaction between the treatment groups and factors was tested for each symptom-related factor using a logistic regression analysis. Each interaction was to be included in the model when significance was detected.

Values of the UPDRS part III score at the final evaluation were imputed using a last observation carried forward (LOCF) method. All analyses were made using SAS version 9.3 (SAS institute, Cary, N.C., USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

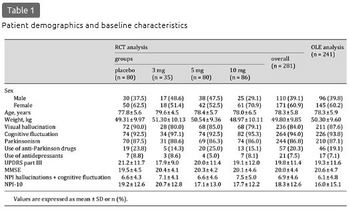

The demographic and baseline characteristics of the patients included in this analysis are summarized in table 1. The phase 2 RCT enrolled 140 patients. Of 123 patients who completed the RCT, 108 patients were enrolled in the phase 2 OLE, 81 of whom completed the study. The phase 3 study enrolled 142 patients; the RCT and OLE were completed by 111 and 100 patients, respectively.

Of the patients included in the RCT analyses, females accounted for 60.9%. The mean age was 78.3 (range 57-95) years; all but 2 patients were 65 years or older. Anti-Parkinson drugs (levodopa or dopamine agonists) were used by 20.3% (57/281) with the mean ± standard deviation (SD) levodopa equivalent dose [33] of 262.0 ± 179.8 mg/day at baseline, and the dosages were not changed during the RCTs. No patients were on antipsychotics. The mean scores for the MMSE and UPDRS part III at baseline were 20.0 and 19.8 points, respectively. The characteristics in the OLE analysis were similar. During the OLEs, levodopa or dopamine agonists were started by 9.1% of patients (22/241), with the dose being increased in 6.6% (16/241) and decreased in 1.2% (3/241).

Analysis of RCTs

Incidence of Extrapyramidal AEs

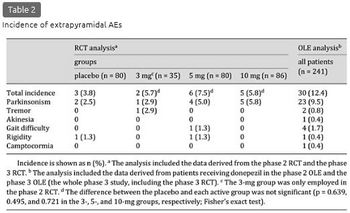

The incidence of extrapyramidal AEs was 3.8% (3/80), 5.7% (2/35), 7.5% (6/80), and 5.8% (5/86) in the placebo, 3-, 5-, and 10-mg groups, respectively, and 6.5% (13/201) in the combined donepezil group, with no significant difference from the placebo group (p = 0.639, 0.495, 0.721, and 0.569 in the 3-, 5-, and 10-mg and combined donepezil group, respectively) (table 2). Most of the extrapyramidal AEs were reported as parkinsonism, the incidence of which was somewhat higher in the combined donepezil group [5.0% (10/201)] than in the placebo group [2.5% (2/80)], but the difference was not significant (p = 0.519). Severity was mild or moderate in all cases, and none were serious. Extrapyramidal AEs that led to discontinuation were reported in 3 patients as parkinsonism and were relieved after discontinuation: 2 patients in the 5-mg group (1 patient while receiving 3 mg) and 1 patient in the 10-mg group while receiving 3 mg.

UPDRS Part III Score

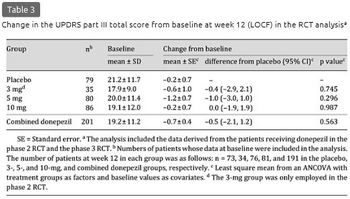

The mean ± SD change in the UPDRS part III total score at week 12 (LOCF) was -0.2 ± 4.3, -0.5 ± 7.4, -1.2 ± 6.8, and -0.1 ± 5.9 in the placebo, 3-, 5-, and 10-mg groups, respectively, and -0.6 ± 6.5 in the combined donepezil group (table 3). The score was rather decreased in each treatment group from baseline, with no significant differences between the placebo and any active groups. Data at the final evaluation prior to week 12 from 30 patients were imputed using the LOCF method, but the results at week 12 of the observed case analysis were very similar to the results of the LOCF analysis (data not shown). Among the UPDRS part III subscales, the mean ± SD score decrease in rigidity was significantly larger in the 5-mg group (-0.8 ± 2.2) than in the placebo group (-0.2 ± 2.0, p = 0.030), although significant differences were not found in the 3- and 10-mg groups for either this or other items (table 4).

Analysis of Long-Term Administration

Incidence of Extrapyramidal AEs

Extrapyramidal AEs were reported by 12.4% (30/241) of patients (table 2). The incidence did not change over time for 52 weeks; the incidence in weeks 0-12, >12-24, >24-36, and >36-52 was 4.4% (9/204), 2.3% (4/173), 3.1% (5/161), and 6.4% (10/157), respectively (note that the placebo group during the phase 3 RCT was excluded from this calculation due to a difference in the administration period).

One severe AE was reported by 1 patient as parkinsonism, and all other AEs were mild or moderate in severity. No serious AEs were reported. AEs that led to discontinuation were reported in 4 patients as parkinsonism. AEs that led to a dose reduction were reported in 4 patients: 3 as parkinsonism and 1 as akinesia. All of these AEs recovered or were relieved after dose reduction or discontinuation, except for the single case of parkinsonism which led to discontinuation after dose reduction in the phase 2 OLE. Most of the extrapyramidal AEs that led to neither discontinuation nor dose reduction of the study drug were treated by start or dose increment of anti-Parkinson drugs [72.7% (16/22)].

UPDRS Part III Score

The mean ± SD change in the UPDRS part III total score from baseline was -0.7 ± 6.5, -0.2 ± 8.6, and 0.1 ± 8.4 at weeks 24, 52, and 52 (LOCF, n = 197, 179, and 227), respectively. The absolute magnitude of the mean change was small, ranging from -0.7 to 0.1, with no significant difference from baseline at any of the evaluation points (p = 0.145, 0.768, and 0.794, respectively).

Exploration for Potential Factors Affecting Extrapyramidal Symptoms

RCT Analysis

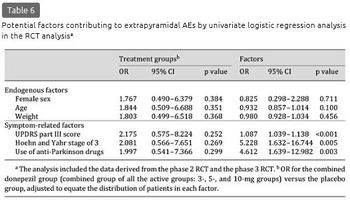

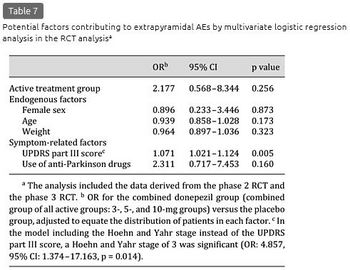

The incidence of extrapyramidal AEs did not differ according to the potential endogenous factors (table 5). Calculated by symptom-related factors, the incidence tended to be higher in the subgroups of the 5- and 10-mg groups with a UPDRS part III score above or equal to the median, a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3, and use of anti-Parkinson drugs, relative to the incidence in the same subgroups of the placebo group and their respective counterparts in the 5- and 10-mg groups, even with an overall small incidence. The results of the univariate logistic regression analysis are shown in table 6. No significant interactions were detected between the treatment group and the symptom-related factors (UPDRS part III score, Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3, and use of anti-Parkinson drugs: p = 0.920, 0.949, and 0.354, respectively). The UPDRS part III score [odds ratio (OR): 1.087, p < 0.001], Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3 (OR: 5.228, p = 0.005), and use of anti-Parkinson drugs (OR: 4.612, p = 0.003) were the significant factors contributing to the extrapyramidal AEs. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the UPDRS part III score was the significant factor (OR: 1.071, p = 0.005) (table 7). In the model including the Hoehn and Yahr stage instead of the UPDRS part III score, a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3 was significant (OR: 4.857, p = 0.014). In the subgroups of the active drug groups with use of anti-Parkinson drugs, the mean levodopa equivalent doses were comparable between patients with and without extrapyramidal AEs (228.6 and 262.9 mg, respectively; p = 0.679).

Long-Term Studies

The incidence of the extrapyramidal AEs did not differ greatly by the endogenous factors (table 5). Among the symptom-related factors, the incidence tended to be higher in the subgroups with a UPDRS part III score above or equal to the median, a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3, and use of anti-Parkinson drugs. In the univariate logistic regression analysis, the UPDRS part III score [OR: 1.052, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.019-1.087, p = 0.002], a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3 (OR: 5.126, 95% CI: 2.228-11.794, p < 0.001), use of anti-Parkinson drugs (OR: 4.125, 95% CI: 1.831-9.293, p < 0.001), and age (OR: 0.931, 95% CI: 0.872-0.993, p = 0.030) were the significant factors. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the UPDRS part III score (OR: 1.043, 95% CI: 1.007-1.080, p = 0.020) and use of anti-Parkinson drugs (OR: 2.581, 95% CI: 1.058-6.298, p = 0.037) were the significant factors. In the model including the Hoehn and Yahr stage instead of the UPDRS part III score, a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3 (OR: 5.561, 95% CI: 2.179-14.192, p < 0.001) and age (OR: 0.904, 95% CI: 0.834-0.980, p = 0.014) were significant. In the subgroups with use of anti-Parkinson drugs, the mean levodopa equivalent doses were comparable between patients with and without extrapyramidal AEs (265.4 and 271.5 mg, respectively; p = 0.925).

Discussion

This study explored the presence of any possible influence of DLB treatment with donepezil on extrapyramidal symptoms using two pooled datasets. In the RCT analysis, the difference in the incidence of extrapyramidal AEs between the active and placebo groups was minimal, and there was no tendency for a dose-dependent increase in the incidence. In the OLE analysis, none of the extrapyramidal AEs were serious. AEs that led to discontinuation or dose reduction were reported only in 8 patients (3.3%), all of which except for one case of parkinsonism recovered or were relieved after discontinuation or dose reduction. Moreover, the possibility of delayed onset or worsening of extrapyramidal AEs with long-term treatment appears low. In contrast to the concern based on the classical dopaminergic-cholinergic imbalance theory about worsening of extrapyramidal symptoms by cholinergic enhancement, these results suggest that patients with DLB can benefit from donepezil, which has a well-established efficacy on cognitive and psychiatric functions [12,13,14,15], with a minimal risk for extrapyramidal symptoms. The absence of an influence of ChEIs, including donepezil, on parkinsonism has been reported in previous studies, along with improvement in a few of these studies, which reinforces the interpretations drawn from this analysis [7,10,11,22,34]. Our finding is also in accordance with accumulating evidence of cholinergic involvement in PD; degeneration of multiple cholinergic projection systems occurs early in PD [35], cholinergic degeneration plays a role in some aspects of motor symptoms including postural control [36] and gait [37], and treatment with donepezil produces reductions in the number of falls in frequently falling patients with PD [38].

In contrast to our study, a worsening of parkinsonism after ChEI administration has been reported in some studies [18,19,20,21]. Moreover, compared with AD, extrapyramidal symptoms are considered to occur more frequently in patients with DLB. In a 24-week RCT and a 52-week OLE of donepezil in patients with severe AD in Japan, parkinsonism was reported with less than a 5.0% incidence [39,40]. The incidence in the present study is seemingly higher, although the events cannot necessarily be attributed to donepezil but to disease progression.

In the present study, baseline severity of parkinsonism (i.e. the UPDRS part III score, a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3, and use of anti-Parkinson drugs) was identified as a predisposing factor for worsening of parkinsonism. Donepezil was not a contributing factor. There was no significant interaction between donepezil and baseline severity. These results suggest that extrapyramidal AEs can mostly be attributed to progression in the relatively severe stage.

Studies of ChEIs for patients with PDD, which is in the same spectrum of Lewy body disease as DLB, reported a slightly higher incidence of extrapyramidal AEs in the active than in the placebo group (tremor: 3.9 and 10.2% in the placebo and rivastigmine groups, respectively [41]; PD: 6.9, 10.8, and 10.4%, and tremor: 2.9, 7.2, and 7.1% in the placebo and donepezil 5- and 10-mg groups, respectively [42]), although both studies concluded that the active treatment was well tolerated. These studies may enable us to delineate the similar safety profile of ChEIs in patients with DLB manifesting relatively severe extrapyramidal symptoms and in those with PDD.

In any case, careful attention is certainly required in treating DLB with donepezil. Particular attention should be placed on patients who manifest extrapyramidal symptoms that restrict their daily living activities and who require pharmacological treatment. Nevertheless, even after the occurrence or worsening of these symptoms, dose reduction or discontinuation, or addition of anti-Parkinson drugs may prevent further worsening and lead to recovery or relief.

An interpretation of this analysis may require consideration of several points. First, the present analysis may not encompass all of the possible factors that may affect the symptoms in treatment with donepezil. Second, the analysis is based on the data obtained under a clinical trial setting where the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria employed may have curtailed the variety of patient characteristics which may be encountered in a real-life setting. Third, patients with very severe parkinsonism of a Hoehn and Yahr stage ≥4 were not included, and thus the present findings cannot be extrapolated to those patients. Finally, the recording of extrapyramidal AEs and UPDRS part III scoring might be confounded due to interrater variability in the assessments in multicenter studies where both neurologists and psychiatrists participated, although a rater training and elaborate monitoring were conducted to reduce the concern. Future studies which overcome all of these possible limitations may be warranted.

In conclusion, donepezil can treat DLB effectively and safely without relevant worsening of extrapyramidal symptoms. However, its administration to patients whose daily living activities are restricted and for whom pharmacotherapy is required due to parkinsonism necessitates care regarding symptom progression. In case of the occurrence or progression of symptoms, a dose reduction or discontinuation, or addition of anti-Parkinson drugs is considered as an effective approach.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and caregivers for their participation in the study; all investigators and their site staff for their contributions; Clinical Study Support, Inc., for their editorial assistance in preparing this manuscript, and the Eisai study team for their assistance. The studies and analyses were sponsored by Eisai Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). The sponsor was involved in the study designing, the collection and analysis of data, and review of the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

E.M. received personal fees from Eisai during the conduct of the studies; grants and personal fees from Eisai, Daiichi Sankyo, and FUJIFILM RI, and personal fees from Janssen, Johnson and Johnson, Lundbeck, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Nihon Medi-Physics, and Medtronic outside the submitted work. All grants were for his department, and he received them as the director of the department. M.I. received personal fees from Eisai during the conduct of the studies; grants and personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, FUJIFILM RI, Janssen, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda, and Tsumura, and personal fees from MSD and Ono Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. All grants were for his department, and he received them as the director of the department. M.N., H.M., and H.Y. are employees of Eisai. K.K. received personal fees from Eisai during the conduct of the studies and personal fees from Tsumura, Eisai, Janssen, FUJIFILM RI, Novartis, Nihon Medi-Physics, Daiichi Sankyo, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka, and Dainippon Sumitomo outside the submitted work.

References

(省略)

Abstract

Background/Aims: The aim of this study was to clarify the effects of donepezil on extrapyramidal symptoms in patients with dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB). Methods: Using pooled datasets from phase 2 and 3, 12-week randomized, placebo-controlled trials (RCT, n = 281) and 52-week open-label long-term extension trials (OLE, n = 241) of donepezil in DLB, the effects of donepezil on the incidence of extrapyramidal adverse events (AEs) and on the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) part III were assessed, and potential baseline factors affecting the AEs were explored. Results: The RCT analysis did not show significant differences between the placebo and active (3, 5, and 10 mg donepezil) groups in extrapyramidal AE incidence (3.8 and 6.5%, p = 0.569) and change in the UPDRS (mean ± SD: -0.2 ± 4.3 and -0.6 ± 6.5, p = 0.562). In the OLE analysis (5 and 10 mg donepezil), the incidence did not increase chronologically; all AEs leading to a dose reduction or discontinuation except one were relieved. The UPDRS was unchanged for 52 weeks. An exploratory multivariate logistic regression analysis of the RCTs revealed that donepezil treatment was not a significant factor affecting the AEs. Baseline severity of parkinsonism was a predisposing factor for worsening of parkinsonism without significant interactions between donepezil and baseline severity. Conclusion: DLB can safely be treated with donepezil without relevant worsening of extrapyramidal symptoms, but treatment requires careful attention to symptom progression when administered to patients with relatively severe parkinsonism.

Introduction

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is the second most common form of senile dementia following Alzheimer's disease (AD) [1]. The core clinical features of DLB include neuropsychiatric symptoms and parkinsonism as well as cognitive impairment characterized by deficits in attention, executive function, and visual perception [2]. The cholinergic loss and a choline acetyltransferase activity deficit with preserved postsynaptic cortical muscarinic and nicotinic receptors [3,4,5] rationalizes the use of cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs) in DLB. The favorable potential of ChEls such as galantamine, rivastigmine, and donepezil has been demonstrated in previous studies [6,7,8,9,10,11]. The phase 2 and 3 trials of donepezil in patients with DLB have added to the accumulating evidence of the efficacy and safety of donepezil in terms of cognitive, behavioral, and global function in DLB, even for long durations, without increasing the risk of clinically significant safety events [12,13,14,15].

It has been reported that 25-50% of patients with DLB have parkinsonism at the time of diagnosis and that 75-80% of such patients eventually develop it [16], although the exact proportion is still controversial. In a natural course, the symptoms could worsen with a speed comparable to Parkinson's disease (PD) [17]. The cholinergic interneurons synapse on the GABAergic striatal neurons that project to the globus pallidus. The cholinergic actions inhibit striatal cells of the direct pathway and excite striatal cells of the indirect pathway. Thus, ChEIs augment cholinergic function, which may oppose the effects of dopamine on the direct and indirect pathways exacerbating parkinsonism in DLB, in which nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons have been lost [18,19,20,21]. On purely theoretical grounds, ChEI administration targeting cognitive impairment and behavioral symptoms may exacerbate parkinsonism. Despite studies showing that ChEIs did not affect parkinsonism and which did not replicate the possible untoward effects in patients with DLB or PD dementia (PDD) [22,23], concerns over a possible influence on the extrapyramidal symptoms still linger due to a shortage of evidence from large-scale, placebo-controlled, or long-term studies especially in DLB and require further confirmation.

As in diseases like DLB treatment for one symptom may precipitate others [24] and the combination or severity of the associated multiple, multi-dimensional symptoms varies by patient, a large-scale comprehensive study is essential. Our trials of donepezil in patients with DLB consist of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials (RCT) and two open-label long-term extension studies (OLE) and enrolled a large group of patients that may embody patients with diverse demographic characteristics and clinical symptom manifestations, which the current diagnosis of probable DLB may encompass. We therefore developed two types of comprehensive pooled datasets from two RCTs and two OLEs of donepezil for DLB. RCTs provide information with minimized bias, while OLEs involve more patient-years of exposure to donepezil and may thus disclose adverse effects which are not observed in the parent RCTs. Using these datasets of the largest scale ever in DLB, we analyzed the effect of donepezil on the occurrence and worsening of extrapyramidal symptoms in patients with DLB.

Methods

Design of the Phase 2 and 3 Studies

This analysis pooled the data from the phase 2 and 3 studies of donepezil for DLB conducted in Japan. The phase 2 studies, consisting of a RCT (clinicaltrials.gov reference: NCT00543855) and a subsequent OLE (clinicaltrials.gov reference: NCT00598650), were conducted as two sequential protocols. A 12-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled exploratory study (phase 2 RCT) was first conducted to investigate the efficacy and safety of donepezil at 3, 5, and 10 mg/day starting in 2007 (fig. 1a) [12]. In the patients who completed this RCT, the safety and efficacy of long-term administration at 5 mg were further investigated in the following 52-week OLE (phase 2 OLE) (fig. 1b) [13]. The phase 3 study (clinicaltrials.gov reference: NCT01278407) was conducted as a single protocol consisting of an RCT phase and a subsequent OLE phase. A 16-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled comparative study consisting of a 12-week confirmatory phase (phase 3 RCT) (fig. 1a) [14] and a 4-week transition period and a subsequent 36-week OLE phase were conducted starting in 2011 for a total duration of 52 weeks (phase 3 OLE) (fig. 1b) [15]. The aim was to confirm the superiority of donepezil at 5 and 10 mg/day for 12 weeks over placebo with regard to both cognitive function and behavioral symptoms and to evaluate the safety and efficacy of long-term administration of 10 mg/day for 52 weeks. Each study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocols were approved by the institutional review board at each participating center.

Patients

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same in both RCTs. The inclusion criteria were patients aged ≥50 years with probable DLB fulfilling the consensus diagnostic criteria [2], with mild to moderate-severe dementia [10-26 points on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Clinical Dementia Rating ≥0.5], behavioral symptoms or cognitive fluctuation [Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)-plus ≥8 (rated on 12 items: original 10 NPI items + sleep [25,26] + Cognitive Fluctuation Inventory [27,28])], and with caregivers who could routinely stay with the patients, provide information for this study, assist with treatment compliance, and escort them to required visits.

The exclusion criteria included PD that was diagnosed at least 1 year prior to the onset of dementia; focal vascular lesions on an MRI or CT that might cause cognitive impairment; other neurological or psychiatric diseases; complications or a history of severe gastrointestinal ulcers, severe asthma, or obstructive pulmonary disease; systolic hypotension (<90 mm Hg); bradycardia (<50 bpm); sick sinus syndrome; atrial or atrioventricular conduction block; QT interval prolongation (≥450 ms); severe parkinsonism (Hoehn and Yahr stage ≥4) [29], and treatment with ChEIs or any investigational drug within 3 months prior to screening. ChEIs, antipsychotics, and anti-Parkinson drugs were not allowed during the study, except for levodopa and dopamine agonists, of which only stable doses were allowed during the RCTs.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient (if at all possible) and his/her primary family member before initiating the study procedures.

Donepezil Administration

In the phase 2 RCT, the patients were randomized to placebo, 3, 5, or 10 mg/day of donepezil (placebo, 3-, 5-, and 10-mg groups) (fig. 1a). In the subsequent phase 2 OLE, all patients received donepezil at 5 mg/day (fig. 1b). Donepezil administration in the 5- and 10-mg groups started with a 2-week titration period with a 3-mg dose, which was applied in all of the studies.

In the phase 3 RCT, the patients were randomized to placebo, 5, or 10 mg/day (placebo, 5-, or 10-mg group) (fig. 1a). Since the phase 3 study incorporated the RCT and OLE phases, the duration of donepezil administration in the phase 3 OLE differed by treatment group: 52 weeks for the 5- and 10-mg groups (10 mg administration from week 24 and 6, respectively) with a 12-week overlap with the phase 3 RCT, and 36 weeks for the placebo group (3 mg titration from week 16, 5 mg administration from week 18, and 10 mg from week 24) (fig. 1b).

In the OLEs, a dose reduction to 3 mg in the phase 2 OLE or to 5 mg after week 24 in the phase 3 OLE was allowed upon emergence of a safety concern.

Summary of the Results of the Phase 2 and 3 Studies

The results of the phase 2 and 3 studies are reported in detail elsewhere [12,13,14,15]. Briefly, in phase 2, the RCT showed that donepezil significantly improved cognitive, behavioral, and global functions with good tolerability, and the OLE demonstrated that administration was well tolerated even for a long duration and that the effect on cognitive and behavioral impairment was maintained for up to 52 weeks. In phase 3, although the RCT failed to confirm a superiority concerning the behavioral symptoms over placebo, it confirmed the efficacy concerning cognitive function (one of the co-primary endpoints) without serious safety concerns. The OLE demonstrated a lasting improvement in cognitive function for up to 52 weeks, without increasing the risk of clinically significant safety events.

Datasets

The safety data regarding extrapyramidal symptoms derived from these studies were pooled in two ways: RCT and OLE (fig. 1). The datasets of the two RCTs were pooled and analyzed according to allocated treatment during the 12-week period: placebo, 3-, 5-, or 10-mg groups (n = 281) (fig. 1a). The dataset derived from all patients receiving donepezil via long-term administration [i.e. phase 2 OLE and phase 3 OLE (whole period of phase 3: RCT + OLE)] was pooled and analyzed (n = 241) (fig. 1b).

Assessment of Extrapyramidal Symptoms

The influence on extrapyramidal symptoms was evaluated according to the incidence of extrapyramidal adverse events (AEs) and the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) part III [30]. To reduce interrater and intrarater variability, an advanced rater training was conducted, a fixed rater was involved in the assessment of each patient in principle, and an elaborate monitoring was made throughout the study period. Of all the AEs which occurred during the studies (coded according to the Preferred Terms of the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities), the following were identified as extrapyramidal AEs after discussion by the central committee: parkinsonism, rigidity, tremor, camptocormia, gait difficulty, and akinesia. The UPDRS part III was conducted every 12 weeks in the phase 2 RCT and in phase 3, and every 24 weeks in the phase 2 OLE.

Statistical Analysis

This secondary analysis was based on the safety analysis set of each study, which comprised all patients who received at least one dose of donepezil and had safety assessment data. For the analysis of the RCTs, the incidence of extrapyramidal AEs was summarized by treatment group and compared between the placebo and each active group using Fisher's exact test. The change in the UPDRS part III total and subscale score from baseline was compared between the placebo and each treatment group using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with the baseline values as covariates. Subscales were predefined as the following four symptoms: tremor, akinesia, rigidity, and postural instability and gait difficulty, with score ranges of 0-28, 0-36, 0-20, and 0-16, respectively [31,32]. For the analysis of OLEs, the incidence of extrapyramidal AEs was calculated. The UPDRS part III scores were analyzed using Student's paired t test.

To identify any potential baseline factors that may contribute to the extrapyramidal AEs, the incidence was calculated for subgroups stratified by the potential factors, and univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were subsequently conducted. Potential factors included endogenous factors (sex, age, and body weight) and symptom-related factors [UPDRS part III score, Hoehn and Yahr stage (≤2 or 3), and use of anti-Parkinson drugs (use or nonuse)]. In multivariate analyses, either the UPDRS part III score or the Hoehn and Yahr stage was included in the model because of the high correlation between them. In the analysis of the RCTs, the interaction between the treatment groups and factors was tested for each symptom-related factor using a logistic regression analysis. Each interaction was to be included in the model when significance was detected.

Values of the UPDRS part III score at the final evaluation were imputed using a last observation carried forward (LOCF) method. All analyses were made using SAS version 9.3 (SAS institute, Cary, N.C., USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

The demographic and baseline characteristics of the patients included in this analysis are summarized in table 1. The phase 2 RCT enrolled 140 patients. Of 123 patients who completed the RCT, 108 patients were enrolled in the phase 2 OLE, 81 of whom completed the study. The phase 3 study enrolled 142 patients; the RCT and OLE were completed by 111 and 100 patients, respectively.

Of the patients included in the RCT analyses, females accounted for 60.9%. The mean age was 78.3 (range 57-95) years; all but 2 patients were 65 years or older. Anti-Parkinson drugs (levodopa or dopamine agonists) were used by 20.3% (57/281) with the mean ± standard deviation (SD) levodopa equivalent dose [33] of 262.0 ± 179.8 mg/day at baseline, and the dosages were not changed during the RCTs. No patients were on antipsychotics. The mean scores for the MMSE and UPDRS part III at baseline were 20.0 and 19.8 points, respectively. The characteristics in the OLE analysis were similar. During the OLEs, levodopa or dopamine agonists were started by 9.1% of patients (22/241), with the dose being increased in 6.6% (16/241) and decreased in 1.2% (3/241).

Analysis of RCTs

Incidence of Extrapyramidal AEs

The incidence of extrapyramidal AEs was 3.8% (3/80), 5.7% (2/35), 7.5% (6/80), and 5.8% (5/86) in the placebo, 3-, 5-, and 10-mg groups, respectively, and 6.5% (13/201) in the combined donepezil group, with no significant difference from the placebo group (p = 0.639, 0.495, 0.721, and 0.569 in the 3-, 5-, and 10-mg and combined donepezil group, respectively) (table 2). Most of the extrapyramidal AEs were reported as parkinsonism, the incidence of which was somewhat higher in the combined donepezil group [5.0% (10/201)] than in the placebo group [2.5% (2/80)], but the difference was not significant (p = 0.519). Severity was mild or moderate in all cases, and none were serious. Extrapyramidal AEs that led to discontinuation were reported in 3 patients as parkinsonism and were relieved after discontinuation: 2 patients in the 5-mg group (1 patient while receiving 3 mg) and 1 patient in the 10-mg group while receiving 3 mg.

UPDRS Part III Score

The mean ± SD change in the UPDRS part III total score at week 12 (LOCF) was -0.2 ± 4.3, -0.5 ± 7.4, -1.2 ± 6.8, and -0.1 ± 5.9 in the placebo, 3-, 5-, and 10-mg groups, respectively, and -0.6 ± 6.5 in the combined donepezil group (table 3). The score was rather decreased in each treatment group from baseline, with no significant differences between the placebo and any active groups. Data at the final evaluation prior to week 12 from 30 patients were imputed using the LOCF method, but the results at week 12 of the observed case analysis were very similar to the results of the LOCF analysis (data not shown). Among the UPDRS part III subscales, the mean ± SD score decrease in rigidity was significantly larger in the 5-mg group (-0.8 ± 2.2) than in the placebo group (-0.2 ± 2.0, p = 0.030), although significant differences were not found in the 3- and 10-mg groups for either this or other items (table 4).

Analysis of Long-Term Administration

Incidence of Extrapyramidal AEs

Extrapyramidal AEs were reported by 12.4% (30/241) of patients (table 2). The incidence did not change over time for 52 weeks; the incidence in weeks 0-12, >12-24, >24-36, and >36-52 was 4.4% (9/204), 2.3% (4/173), 3.1% (5/161), and 6.4% (10/157), respectively (note that the placebo group during the phase 3 RCT was excluded from this calculation due to a difference in the administration period).

One severe AE was reported by 1 patient as parkinsonism, and all other AEs were mild or moderate in severity. No serious AEs were reported. AEs that led to discontinuation were reported in 4 patients as parkinsonism. AEs that led to a dose reduction were reported in 4 patients: 3 as parkinsonism and 1 as akinesia. All of these AEs recovered or were relieved after dose reduction or discontinuation, except for the single case of parkinsonism which led to discontinuation after dose reduction in the phase 2 OLE. Most of the extrapyramidal AEs that led to neither discontinuation nor dose reduction of the study drug were treated by start or dose increment of anti-Parkinson drugs [72.7% (16/22)].

UPDRS Part III Score

The mean ± SD change in the UPDRS part III total score from baseline was -0.7 ± 6.5, -0.2 ± 8.6, and 0.1 ± 8.4 at weeks 24, 52, and 52 (LOCF, n = 197, 179, and 227), respectively. The absolute magnitude of the mean change was small, ranging from -0.7 to 0.1, with no significant difference from baseline at any of the evaluation points (p = 0.145, 0.768, and 0.794, respectively).

Exploration for Potential Factors Affecting Extrapyramidal Symptoms

RCT Analysis

The incidence of extrapyramidal AEs did not differ according to the potential endogenous factors (table 5). Calculated by symptom-related factors, the incidence tended to be higher in the subgroups of the 5- and 10-mg groups with a UPDRS part III score above or equal to the median, a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3, and use of anti-Parkinson drugs, relative to the incidence in the same subgroups of the placebo group and their respective counterparts in the 5- and 10-mg groups, even with an overall small incidence. The results of the univariate logistic regression analysis are shown in table 6. No significant interactions were detected between the treatment group and the symptom-related factors (UPDRS part III score, Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3, and use of anti-Parkinson drugs: p = 0.920, 0.949, and 0.354, respectively). The UPDRS part III score [odds ratio (OR): 1.087, p < 0.001], Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3 (OR: 5.228, p = 0.005), and use of anti-Parkinson drugs (OR: 4.612, p = 0.003) were the significant factors contributing to the extrapyramidal AEs. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the UPDRS part III score was the significant factor (OR: 1.071, p = 0.005) (table 7). In the model including the Hoehn and Yahr stage instead of the UPDRS part III score, a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3 was significant (OR: 4.857, p = 0.014). In the subgroups of the active drug groups with use of anti-Parkinson drugs, the mean levodopa equivalent doses were comparable between patients with and without extrapyramidal AEs (228.6 and 262.9 mg, respectively; p = 0.679).

Long-Term Studies

The incidence of the extrapyramidal AEs did not differ greatly by the endogenous factors (table 5). Among the symptom-related factors, the incidence tended to be higher in the subgroups with a UPDRS part III score above or equal to the median, a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3, and use of anti-Parkinson drugs. In the univariate logistic regression analysis, the UPDRS part III score [OR: 1.052, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.019-1.087, p = 0.002], a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3 (OR: 5.126, 95% CI: 2.228-11.794, p < 0.001), use of anti-Parkinson drugs (OR: 4.125, 95% CI: 1.831-9.293, p < 0.001), and age (OR: 0.931, 95% CI: 0.872-0.993, p = 0.030) were the significant factors. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, the UPDRS part III score (OR: 1.043, 95% CI: 1.007-1.080, p = 0.020) and use of anti-Parkinson drugs (OR: 2.581, 95% CI: 1.058-6.298, p = 0.037) were the significant factors. In the model including the Hoehn and Yahr stage instead of the UPDRS part III score, a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3 (OR: 5.561, 95% CI: 2.179-14.192, p < 0.001) and age (OR: 0.904, 95% CI: 0.834-0.980, p = 0.014) were significant. In the subgroups with use of anti-Parkinson drugs, the mean levodopa equivalent doses were comparable between patients with and without extrapyramidal AEs (265.4 and 271.5 mg, respectively; p = 0.925).

Discussion

This study explored the presence of any possible influence of DLB treatment with donepezil on extrapyramidal symptoms using two pooled datasets. In the RCT analysis, the difference in the incidence of extrapyramidal AEs between the active and placebo groups was minimal, and there was no tendency for a dose-dependent increase in the incidence. In the OLE analysis, none of the extrapyramidal AEs were serious. AEs that led to discontinuation or dose reduction were reported only in 8 patients (3.3%), all of which except for one case of parkinsonism recovered or were relieved after discontinuation or dose reduction. Moreover, the possibility of delayed onset or worsening of extrapyramidal AEs with long-term treatment appears low. In contrast to the concern based on the classical dopaminergic-cholinergic imbalance theory about worsening of extrapyramidal symptoms by cholinergic enhancement, these results suggest that patients with DLB can benefit from donepezil, which has a well-established efficacy on cognitive and psychiatric functions [12,13,14,15], with a minimal risk for extrapyramidal symptoms. The absence of an influence of ChEIs, including donepezil, on parkinsonism has been reported in previous studies, along with improvement in a few of these studies, which reinforces the interpretations drawn from this analysis [7,10,11,22,34]. Our finding is also in accordance with accumulating evidence of cholinergic involvement in PD; degeneration of multiple cholinergic projection systems occurs early in PD [35], cholinergic degeneration plays a role in some aspects of motor symptoms including postural control [36] and gait [37], and treatment with donepezil produces reductions in the number of falls in frequently falling patients with PD [38].

In contrast to our study, a worsening of parkinsonism after ChEI administration has been reported in some studies [18,19,20,21]. Moreover, compared with AD, extrapyramidal symptoms are considered to occur more frequently in patients with DLB. In a 24-week RCT and a 52-week OLE of donepezil in patients with severe AD in Japan, parkinsonism was reported with less than a 5.0% incidence [39,40]. The incidence in the present study is seemingly higher, although the events cannot necessarily be attributed to donepezil but to disease progression.

In the present study, baseline severity of parkinsonism (i.e. the UPDRS part III score, a Hoehn and Yahr stage of 3, and use of anti-Parkinson drugs) was identified as a predisposing factor for worsening of parkinsonism. Donepezil was not a contributing factor. There was no significant interaction between donepezil and baseline severity. These results suggest that extrapyramidal AEs can mostly be attributed to progression in the relatively severe stage.

Studies of ChEIs for patients with PDD, which is in the same spectrum of Lewy body disease as DLB, reported a slightly higher incidence of extrapyramidal AEs in the active than in the placebo group (tremor: 3.9 and 10.2% in the placebo and rivastigmine groups, respectively [41]; PD: 6.9, 10.8, and 10.4%, and tremor: 2.9, 7.2, and 7.1% in the placebo and donepezil 5- and 10-mg groups, respectively [42]), although both studies concluded that the active treatment was well tolerated. These studies may enable us to delineate the similar safety profile of ChEIs in patients with DLB manifesting relatively severe extrapyramidal symptoms and in those with PDD.

In any case, careful attention is certainly required in treating DLB with donepezil. Particular attention should be placed on patients who manifest extrapyramidal symptoms that restrict their daily living activities and who require pharmacological treatment. Nevertheless, even after the occurrence or worsening of these symptoms, dose reduction or discontinuation, or addition of anti-Parkinson drugs may prevent further worsening and lead to recovery or relief.

An interpretation of this analysis may require consideration of several points. First, the present analysis may not encompass all of the possible factors that may affect the symptoms in treatment with donepezil. Second, the analysis is based on the data obtained under a clinical trial setting where the strict inclusion and exclusion criteria employed may have curtailed the variety of patient characteristics which may be encountered in a real-life setting. Third, patients with very severe parkinsonism of a Hoehn and Yahr stage ≥4 were not included, and thus the present findings cannot be extrapolated to those patients. Finally, the recording of extrapyramidal AEs and UPDRS part III scoring might be confounded due to interrater variability in the assessments in multicenter studies where both neurologists and psychiatrists participated, although a rater training and elaborate monitoring were conducted to reduce the concern. Future studies which overcome all of these possible limitations may be warranted.

In conclusion, donepezil can treat DLB effectively and safely without relevant worsening of extrapyramidal symptoms. However, its administration to patients whose daily living activities are restricted and for whom pharmacotherapy is required due to parkinsonism necessitates care regarding symptom progression. In case of the occurrence or progression of symptoms, a dose reduction or discontinuation, or addition of anti-Parkinson drugs is considered as an effective approach.

Acknowledgments

We thank all patients and caregivers for their participation in the study; all investigators and their site staff for their contributions; Clinical Study Support, Inc., for their editorial assistance in preparing this manuscript, and the Eisai study team for their assistance. The studies and analyses were sponsored by Eisai Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan). The sponsor was involved in the study designing, the collection and analysis of data, and review of the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

E.M. received personal fees from Eisai during the conduct of the studies; grants and personal fees from Eisai, Daiichi Sankyo, and FUJIFILM RI, and personal fees from Janssen, Johnson and Johnson, Lundbeck, Novartis, Ono Pharmaceutical, Nihon Medi-Physics, and Medtronic outside the submitted work. All grants were for his department, and he received them as the director of the department. M.I. received personal fees from Eisai during the conduct of the studies; grants and personal fees from Daiichi Sankyo, Eisai, FUJIFILM RI, Janssen, Nihon Medi-Physics, Novartis, Pfizer, Takeda, and Tsumura, and personal fees from MSD and Ono Pharmaceutical outside the submitted work. All grants were for his department, and he received them as the director of the department. M.N., H.M., and H.Y. are employees of Eisai. K.K. received personal fees from Eisai during the conduct of the studies and personal fees from Tsumura, Eisai, Janssen, FUJIFILM RI, Novartis, Nihon Medi-Physics, Daiichi Sankyo, Ono Pharmaceutical, Otsuka, and Dainippon Sumitomo outside the submitted work.

References

(省略)

2016-10-26 12:15

nice!(0)

コメント(0)

トラックバック(0)

コメント 0